The Sweet Life, Part 1

One of the most respected professions in the eighteenth

century was that of confectioner. Their

skill set elevated them above a mere cook or baker and if very successful in their

craft, they could receive high financial rewards and a social standing denied

to other food professionals. Most

confectioners were employed by the aristocracy or the royal families. Others ran their own businesses in cities and

large towns. They sold luxury table

furnishings and a variety of sweetmeats and treats. There were also books being published to

inform housekeepers and hostesses about the genteel craft of confections. One of the earliest cookbooks published

outside London was a small work on confectionery in 1737. The art of confectionery has been socially

acceptable to high-ranking ladies since the Tudor period when the knowledge of

setting a banquet was a necessary skill.

The expensive nature of the ingredients meant servants were often not

trusted to use the materials and the confectionery work became the

responsibility of the lady of the house making it a genteel and refined

activity.

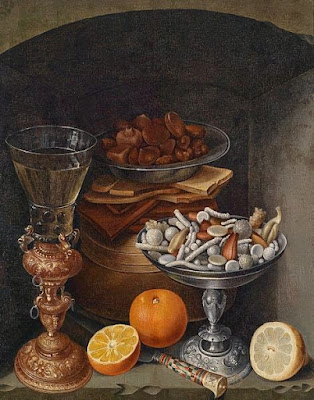

The

basic materials of early confectionery were expensive exotic materials from the

Mediterranean or the Middle East: sugar, citrus fruits, almonds, rosewater and

later chocolate from the New World. At

first many sweats would be imported before Europeans learned the techniques of

making them. Sugar was the most

important ingredient. Sugar cane is

indigenous to Southeast Asia. Romans

knew of it from their trade with Arabia and India but its use had been confined

to medicine therefore Romans used honey as a sweetener in their kitchens. In India and Southeast Asia sugar cane was

chewed to extract the sweet juice. The

development of boiling the juice to make sugar crystals was done in India and

then the technique moved west to Mesopotamia.

The Persians and Arabs used sukkar for treating colds and bronchial

disorders. During the medieval period

Venetian and Genoese traders controlled the trade of Arabic products until the

Portuguese broke this monopoly and started cultivating sugar cane in the Azores

and later Brazil. Centuries of

experimentation and a clearer understanding of this plant transformed it from

medicine and sweetener to preservative then artistic medium. 1

Europeans

were importing sugar from the Arabs as early as the 12th century but

this was a very expensive food stuff like many spices coming from southeast Asia. Plantations were being built on Islands in

the Mediterrean including Cyprus but the demand was low and production small

because of the labor intensive work.

Slaves from the Black Sea area and some from Africa were brought to do

the work of harvesting and boiling. The

Portuguese brought sugar cane plants first to the Canary Islands in the

Atlantic and then by the 15th century explorers like Columbus

brought sugar cane to the New World and plantations grew throughout the

Caribbean and South American colonies using African slave labor to make sugar

cheaper for trade.2

Europeans

were importing sugar from the Arabs as early as the 12th century but

this was a very expensive food stuff like many spices coming from southeast Asia. Plantations were being built on Islands in

the Mediterrean including Cyprus but the demand was low and production small

because of the labor intensive work.

Slaves from the Black Sea area and some from Africa were brought to do

the work of harvesting and boiling. The

Portuguese brought sugar cane plants first to the Canary Islands in the

Atlantic and then by the 15th century explorers like Columbus

brought sugar cane to the New World and plantations grew throughout the

Caribbean and South American colonies using African slave labor to make sugar

cheaper for trade.2

The

apothecary had the most important role in the early history of sugar in

Europe. For northern Europeans remedies

for rheums and fevers from the middle east were enthusiastically adopted. Twisted sticks of pulled sugar called al panad in Arabic were sold as cough

sweets and then other drops made from ground pinenuts, almonds, cinnamon,

cloves, ginger and liquorice were still being prescribed in 17th

century England “for such as those who have Coughs, Ulcers and Consumptions of

the Lungs.”3 Lozenges and medicinal syrups were a mixture

of such things as rosewater, gold leaf and sugar. Quiddany of green walnuts and quince

marmalade could be prescribed for vomiting, weakness of the stomach,

inflammation of the mouth and throat.

Recipes for these home remedies would be found in the same manuscripts

as the preparations of preserves and confectionery. It was the alleged digestive and warming

properties of sugar that gave it an important part in the medieval void or

ending of a state meal. The king or lord

“closed” his overfull stomach by eating comfits (sugar coated spices and seeds)

and drinking a sweet spiced wine called hypocras. The range of sweetmeats consumed

at this “aftercourse” grew dramatically turning into an elaborate sweet banquet

in later centuries. The sweet banquet

grew into a delight for the eye and palette with lavis and dramatic displays of

sweetmeats and sugarwork but the medicinal purpose of soothing the stomach

after a heavy meal still remained. These

marmalades and spice mixtures were the equivalent to our indigestion

tablets. Caraway and aniseed comfits

were two of the most popular comfits along with slivers of cinnamon sticks and

ginger.

Of

course it was also understood that the excessive consumption of sugar was a

health risk but the thought that sweetmeats possessed beneficial medicinal

properties probably helped. Thomas Tyron

in the 17th century stated “great quantities of the Confectioners

Hodge-Podge, and the Cakes, the Buns, the ginger-bread &c. All which do wonderfully fur and abstruct the

passages”. 4 Comfits at first referred

to all kinds of sweetmeats made from fruits, roots, or flowers preserved with

sugar but by the 16th century they were specifically a seed, nut or

small piece of spice enclosed in a round or ovoid mass of sugar. The production of these comfits for the

“void” was the core skill of early confectioners who were also called

comfitmakers. One of the earliest

detailed accounts of comfit making was in Sir Hugh Platt”s “Delights for

Ladies” in 1600. He describes the

equipment needed along with “the arte of comfetmaking, teaching how to cover

all kinds of seeds, fruits or spices with sugar”. In 1820 illustrations of the equipment used

by the confectioner matched the 1600 description, the apparatus did not change

until the 19th century when it became mechanized. The items to be coated would be put in a

balancing pan and coated with layers of a gun Arabic solution to seal in

natural oils and help the sugar adhere.

A copper beading funnel, with a screw thread spigot, regulated the flow

of syrup. As the items dried they would

be put over a gentle heat provided by a chaffing dish and rubbed between hands

to separate them. When completely dry a

ladle would pour a thin syrup into the pan to “pearl” the items. Sieves of different grades made from perforated

leather were used to sort the finished comfits into sizes. If they were to be colored this would be

added to the syrup in the last few coats.

Up to twenty coats of sugar could be layered on items depending on what

type of comfit is being made. Muskadines, or breath fresheners, were made by

scenting sugar paste with musk, rosewater and orris powder and then were cut

into diamond shapes. By the 19th

century other flavors like coffee, chocolate, bergamot and vanilla were used

for these smooth lozenges. Almond

comfits were also flavored with floral essences like rose and orangeflower,

jasmine and bergamot. The density and

temperature of syrup used by the comfitmaker was critical and a whole range of

sugar boils was developed by the medieval Arabs then the Renaissance Italians

but finally published by the French, hence the French names, including Le petit

lisse, all the way to Le caramel, 14 different boiling points of sugar.5

Of

course it was also understood that the excessive consumption of sugar was a

health risk but the thought that sweetmeats possessed beneficial medicinal

properties probably helped. Thomas Tyron

in the 17th century stated “great quantities of the Confectioners

Hodge-Podge, and the Cakes, the Buns, the ginger-bread &c. All which do wonderfully fur and abstruct the

passages”. 4 Comfits at first referred

to all kinds of sweetmeats made from fruits, roots, or flowers preserved with

sugar but by the 16th century they were specifically a seed, nut or

small piece of spice enclosed in a round or ovoid mass of sugar. The production of these comfits for the

“void” was the core skill of early confectioners who were also called

comfitmakers. One of the earliest

detailed accounts of comfit making was in Sir Hugh Platt”s “Delights for

Ladies” in 1600. He describes the

equipment needed along with “the arte of comfetmaking, teaching how to cover

all kinds of seeds, fruits or spices with sugar”. In 1820 illustrations of the equipment used

by the confectioner matched the 1600 description, the apparatus did not change

until the 19th century when it became mechanized. The items to be coated would be put in a

balancing pan and coated with layers of a gun Arabic solution to seal in

natural oils and help the sugar adhere.

A copper beading funnel, with a screw thread spigot, regulated the flow

of syrup. As the items dried they would

be put over a gentle heat provided by a chaffing dish and rubbed between hands

to separate them. When completely dry a

ladle would pour a thin syrup into the pan to “pearl” the items. Sieves of different grades made from perforated

leather were used to sort the finished comfits into sizes. If they were to be colored this would be

added to the syrup in the last few coats.

Up to twenty coats of sugar could be layered on items depending on what

type of comfit is being made. Muskadines, or breath fresheners, were made by

scenting sugar paste with musk, rosewater and orris powder and then were cut

into diamond shapes. By the 19th

century other flavors like coffee, chocolate, bergamot and vanilla were used

for these smooth lozenges. Almond

comfits were also flavored with floral essences like rose and orangeflower,

jasmine and bergamot. The density and

temperature of syrup used by the comfitmaker was critical and a whole range of

sugar boils was developed by the medieval Arabs then the Renaissance Italians

but finally published by the French, hence the French names, including Le petit

lisse, all the way to Le caramel, 14 different boiling points of sugar.5

To be continued…

2 www.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_sugar

3 Salmon, William New London Dispensatory London 1692 p. 636

4 Tryon, Thomas The Good Housewife made a Doctor London 1692 p.155

5 Day, Ivan. “The Art of Confectionery”. www.historicfood.com

Hi Dear,

ReplyDeleteI Like Your Blog Very Much. I see Daily Your Blog, is A Very Useful For me.

You can also Find Best Arabic sweets and confectioneries cafe in London We are one of the best Arabic sweets and confectioneries cafe in the London, UK. Ibaklawa Cafe makes the best quality Mediterranean sweets, such as baklava, cookies, cakes, petitfour and kounfa cheese etc. We serve delicious, fantastic, well served and yummy products.

Visit Now:- https://ibaklawacafe.com/-