The Legend of St. Nicholas

Nicholas of Myra

By Erin Czernecki

Every December we celebrate holiday traditions from

different cultures and backgrounds. Most

Americans accept these traditions and add their own family celebrations. One in particular is interesting: Where does

Santa Claus come from? Is he a real

person? As we will see Santa Claus has been evolving for centuries in many

different European cultures.

The origins of Santa Claus comes from the celebration of

Sinterklaas by the Dutch who inhabited the Hudson River Valley, Manhattan,

parts of New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut during the 17th

century when this area was known as New Netherland. Sinterklaas is a nickname for a man known as

St. Nicholas who was a real person born in Asia Minor. Many of the stories about him were not written

down until 500 years after his death. As

the English started to populate New England and then New York they mixed their

traditions of Father Christmas with Sinterklaas. Other European immigrants came to America and

introduced their own customs of Pere Noel, Samichlaus, Kris Kringle, and other

versions of St. Nicholas. In Central

Europe, St. Nicholas’ helper is called Krampus and keeps track of the good

girls and boys, letting St. Nicholas know who to give presents to.

Nikolaos was born in the 3rd century in a Greek

area of Asia Minor on the Mediterranean Sea called Patara. He was born into a wealthy Christian

family. His parents died in an epidemic

when Nikolaos was still young, and he was sent to live with his uncle, the

bishop of Patara. He inherited a great fortune and gave most of it away to

people in need. [1] Nikolaos did not follow the normal

route for becoming a bishop. When the

bishop of Myra passed away, there was a gathering to select another

bishop. A decision could not be agreed

upon, so they decided that the next day whoever first stepped into the church would

become the next bishop. Nikolaos, now a

grown man, had a dream the night before that he would be a great leader. He woke early in the morning and went immediately

to the church, and was declared Nicholas Bishop of Myra.

In the beginning of the 4th century Emperor

Galerius and then Diocletian, persecuted

the early Christians in the Roman Empire. Many were tortured and put to death for not

worshipping the Emperor. As a well known

bishop, Nicholas was said to have been imprisoned and tortured for his

beliefs. These struggles made his people

love him even more. In 325, under

Emperor Constantine, a gathering of bishops was called in the city of Nicene. He was part of the council that wrote the

Nicene Creed and set the foundation for Christian doctrine. [2]

There are a few myths and legends that have come down through

the generations about Nicholas that establish his appointment to sainthood by

the Catholic church. The most well known

story of St. Nicholas is not a miracle but established him as the anonymous

gift giver that everyone loved. This is

the story of providing dowries for three daughters of a poor family. During

the middle ages when this story started being told this would be a terrible

thing indeed, if the daughters did not have dowries they probably would not be

able to marry. When Nicholas heard of

this family’s trouble he wanted to give them money but anonymously. At night he left a bag of gold at the front

door, or dropped it through the window, depending on the story. The first daughter could marry and as each

daughter came of age he would bring another bag of gold. After the second bag of gold the father was

curious so he waited by the door to see who was leaving the money. Some stories then say that Nicholas went to

the roof and dropped the bag of gold down the chimney, other stories say the

father caught Nicholas, who then made him swear not to tell anyone who had left

the money. [3]

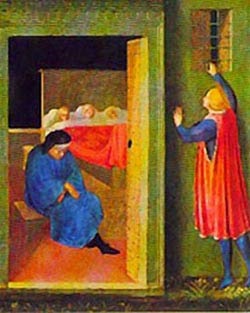

Fra Angelico, 1437

Another miracle attributed to Nicholas for his sainthood is the

calming of the sea. It was said he made

a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and boarded a ship on the Mediterranean Sea. A storm came up and the sailors feared for

their lives. Nicholas prayed and the

seas calmed down. When he returned to

the port city, the news of this miracle had already spread. From this tradition St. Nicholas became the

patron saint of mariners.[4] Many of the mariners considered him their

patron saint and spread the stories of St. Nicholas throughout Europe from the

area of Asia Minor where they started.

The third miracle attributed to Nicholas is bringing three

boys back to life. There were three boys

gathering wheat in a field when they wandered off and went into the nearby

village by themselves. They stopped at a

butcher’s shop to ask for help and food.

This was during a time when the butcher did not have much meat. The butcher killed the three boys, cut up their

bodies and put them in a salting tub to cure and sell them as meat. Later St. Nicholas came through the village

and stopped at the butcher’s house, who invited the bishop in and offers him

refreshment. St. Nicholas points at the

salting tub and tells the butcher that he knows what he did. St. Nicholas brought the boys back to life

and returned them to their families. In

some stories the butcher ran away or St. Nicholas made the butcher walk behind

him in eternal shame. This story brings

about the notion of St. Nicholas as the patron saint of children.[5]

A. Boursier-Mougenot, 1935.

Special baked goods and drinks would also be made for St.

Nicholas Day; Speculaas Koekjes (spice

cookies), Pepernoten (pepper nuts), marzipan, Bisschopswijn (Bishop’s wine),

and hot chocolate (said to be St. Nicholas’ favorite). The spice cookies would be

made with a cookie board or mold of St. Nicholas and other images like a

windmill. [7]

After the Protestant Reformation, in the 16th

century, the Netherlands turned away from Catholic traditions such as the

veneration of saints. Some leaders tried

to stop the celebration of St. Nicholas Day, but it was such a popular holiday

that the people continued to celebrate and focused more on the bringing of

gifts by Sinterklaas and the festivities of the day. Christmas Day would be the time for church

and focusing on the Christ child. In the

17th century when the Dutch came to North America and settled the

areas of New Netherland they brought their cultures and traditions with

them. There is evidence that in the late

17th century bakers were making some of the festive treats for St.

Nicholas Day in December. After the

Revolutionary War, a new interest in the Dutch heritage of New York brought

Sinterklaas to life in America. John

Pintard, founder of the New York Historical Society, hosted its first St.

Nicholas anniversary dinner in 1810.

Artist Alexander Anderson was commissioned to draw an image of the Saint

for the dinner. He was shown as a

religious figure, but he was clearly leaving gifts for the children in their

stockings which were hung by the fireplace to dry.

Alexander Anderson, 1810.

Nothing fixed the image of Santa Claus in American

traditions like the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” written in 1822 by Clement

Moore. He used the basis of Sinterklaas

and added German and Norse legends of an elf-like man delivering presents from

house to house in his sleigh with reindeer.

Moore wrote the story for his family, but it was published in 1823 in

the Troy Sentinal and renamed “The Night Before Christmas”. In 1881 Thomas Nast, a cartoonist, did a

series of drawings for Harper’s Weekly

having Santa living at the North Pole and making toys for the good girls and

boys in his workshop.

Thomas Nast, 1881.

Often this Santa was shown wearing different colored outfits

until the 1940’s when Coca Cola cemented the image of Santa Claus in red and

white trim.[8] Everything else we associate with Santa Claus,

like his elf helpers and Rudolph, were added in the 20th century. Children in the Netherlands and other parts of

Europe still celebrate St. Nicholas as they have for hundreds of years. These

traditions make this time of year all the more special, passing down the

stories and celebrations from one generation to another.

Santa Claus is a culmination of fact and fiction that was

contributed by cultures all over Europe and that incorporates history,

tradition and family valves that has attracted millions over the years. The story continues to evolve. Happy St.

Nicholas Day everyone and Merry Christmas.

1.

Lanzi, Gioia (2004). Saints

and their symbols: recognizing saints in art and in popular images.

Liturgical Press. p. 111.

2.

Wheeler, Joe and Jim Rosenthal. St. Nicholas: A Closer look at Christmas.

Nelson Reference & Electronic, 2005.

3.

“The Story of the Dowries”. www.st.nicholascenter.org.

4.

“St. Nicholas of Myra, Bishop and

Wonder-worker”. www.catholicsm.about.com.

5.

Boursier-Mougenot, A. “Le Legende de Saint

Nicholas”. Tours Maison Mame, 1935.

Comments

Post a Comment